Sometimes we get asked, after posting more than 1000 recipes, are you ever going to run out of ideas? Well rest easy. Chinese cuisine is incredibly varied, and while we’ve covered many recipes from across China, we definitely represent some cuisines more than others. I think it’s time that we talked about the 8 Chinese Cuisines—also known as the 8 Great Cuisines of China—and what they are.

What Are the 8 Chinese Cuisines?

For some people, Chinese food is just Chinese food, and they have a certain idea of what it is—perhaps what they’ve seen at their local restaurant, or what they get when they order takeout.

However, in recent years, we’ve noticed that people are becoming more aware of the regionality of Chinese cuisine, and the variety. You may already know that Mapo Tofu is from Sichuan, or that Mao’s Braised Pork Belly is attributed to Hunan cuisine.

But few people know that there are 8 major Chinese cuisines, sometimes called the 8 great cuisines of China.

These are eight popular cooking traditions, each with its own character, special local ingredients, cooking methods, and tastes that suit the local people, their climate, and culture. While they do not cover the entirety of China’s vast culinary map, they have been identified by Chinese chefs as the most prominent and popular.

REMEMBER: THESE AREN’T CHINA’S ONLY 8 CUISINES!

There are many more. While this article should expand your knowledge of Chinese cooking and show you some of the major dishes from each of the 8 Chinese cuisines, remember, there are many more than just 8.

Other major cuisines that aren’t included in the eight are: Yunnan cuisine, Guizhou cuisine, Shaanxi cuisine, Xinjiang cuisine, and more. Those cuisines deserve exploration too, like Small Pot Rice Noodles from Yunnan or cumin lamb biang biang noodles and Chinese Hamburgers (ròu jiā mó – 肉夹馍) from Shaanxi.

In this article, we will focus on the official 8 Chinese Cuisines, but we work to represent other cuisines through recipes on the blog as well, and perhaps write other articles on them!

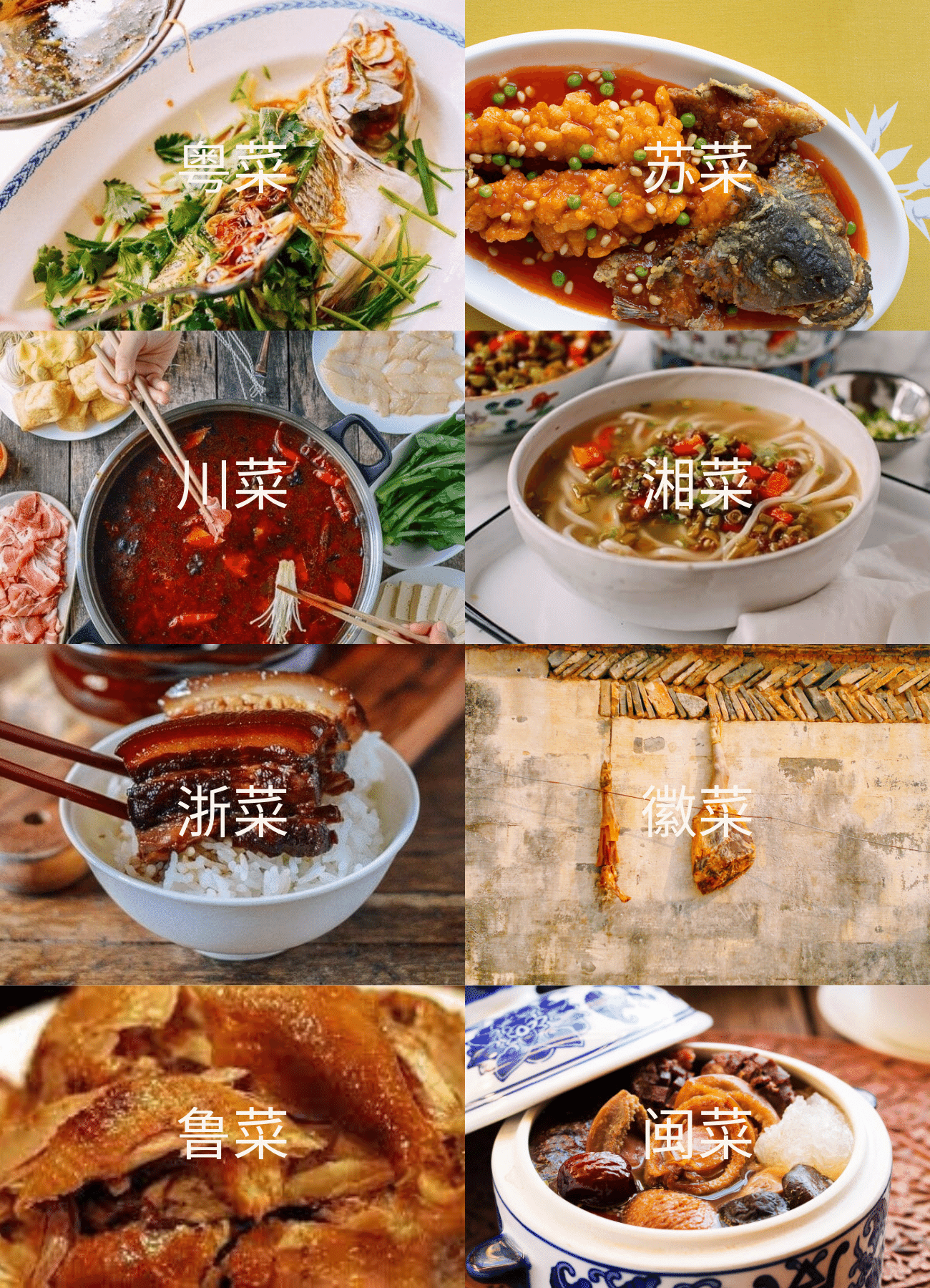

China’s 8 great cuisines include:

- Lu Cai – 鲁菜

- Chuan Cai – 川菜

- Yue Cai – 粤菜

- Su Cai – 苏菜

- Min Cai – 闽菜

- Zhe Cai – 浙菜

- Xiang Cai – 湘菜

- Hui Cai – 徽菜

Each cuisine represents a certain region. As travel becomes more common, the borders around them are becoming more blurred. Each region might take a popular dish like braised pork belly into its own hands, resourcefully creating new classics for the locals.

But while the Chinese culinary scene is continuing to transform, let’s dive deeper into each traditional cuisine and talk about their characteristics. Read about each one below and see which is your favorite!

The 8 Great Cuisines of China: In More Detail

1. Lu (Shandong) CuisinE (鲁菜 – lǔ cài):

With the longest history, Lu Cuisine is ranked #1 of the eight cuisines. It originated in Shandong Province—home of Tsingtao beer and the birthplace of Confucius—in northeastern China.

Because of its long history, it is believed that many of China’s cooking traditions evolved from Lu Cuisine, including Northern Chinese culinary traditions in Beijing and Tianjin.

However, while Lu cuisine has had the biggest influence on Chinese cooking as a whole with its many cooking methods and techniques, it has also experienced the biggest losses. Many dishes have faded into obscurity due to their intricacy as times have changed.

Like the people of Shandong, Lu cuisine is bold, free-spirited, and uses a vast range of cooking techniques and combinations to achieve the ultimate bite.

Shandong is a coastal province, so many dishes employ seafood like squid, shrimp, and sea cucumber. Lu cuisine was also prominent in the ancient emperors’ court, known for its complexity, difficulty, and stringent adherence to freshness and quality of ingredients. Imperial chefs were the iron chefs of the time—highly respected and admired.

Some of Lu Cuisine’s signature dishes include Dezhou Braised Chicken (a whole chicken that is fried and then braised with spices), Scallion Braised Sea Cucumber, and the traditional version of Moo Shu Pork with wood ear mushrooms, cucumber, and scrambled egg.

2. Chuan (Sichuan) Cuisine (川菜 – chuāncài):

Chuan Cuisine, from Sichuan Province, is heavy on oil, salt, and spices—particularly spicy chilies and numbing Sichuan peppercorns.

Its taste is unapologetically in-your-face and can’t be ignored. Some dishes will cause profuse sweating after just a couple of bites, but you still can’t stop eating.

As a spicy food lover myself, I know how addictive it can become when that spiciness hits the right “note.” And that’s why Sichuan cuisine has quickly gained popularity around the world. Its many well-known dishes make Sichuan cuisine one of the most well-represented on our blog!

That’s why it’s so easy to name a large handful of popular Sichuan dishes: Sichuan Hot Pot, Mapo Tofu, Twice Cooked Pork, Fuqi Fei Pian, Kung Pao Chicken, Dan Dan Noodles, and Pork with Garlic Sauce.

All these highly popularized dishes are sure signs of people’s love for Sichuan cuisine, and its role in the Chinese food arena—even overseas.

When people think about Sichuan cuisine, the signature málà (麻辣) combination of numbing Sichuan peppercorns and spicy chili peppers immediately comes to mind.

Chilies feature prominently across many dishes, and red and green Sichuan peppercorns are signature spices in Sichuan cuisine. (Did you know that green Sichuan peppercorns are more numbing than their red counterpart? This is probably why they’re less commonly used.)

Other flavors, including spicy broad bean paste (là dòubàn jiàng – 辣豆瓣酱), “fish fragrant” (yú xiāng – 鱼香) dishes, and “exotic” or “strange” taste dishes (guàiwèi – 怪味) originated in Sichuan cuisine.

3. Yue (Cantonese) Cuisine (粤菜 – yuècài):

While Chuan cuisine may be popular, Yue Cuisine is without a doubt the most popular Chinese cooking style outside of China. Yue Cuisine is more commonly known as Cantonese food, and it hails from the region around the Pearl River Delta, including Guangdong Province, Hong Kong, and Macau.

Why has Yue Cuisine spread to the far reaches of the world? Many of the early Chinese immigrants to the United States, Canada, Australia, Southeast Asia, and Latin America were Cantonese.

Cantonese was the most common dialect spoken in American Chinatowns until recently (nowadays, you’ll also hear Mandarin spoken) and it is the food of this region that evolved into many of the Americanized Chinese takeout dishes you might enjoy today.

Related to Cantonese Cuisine are Chaoshan cuisine (潮汕菜 – cháoshàn cài, also known as teochew or chiuchow cuisine) and Hakka cuisine (客家菜 – kèjiā cài), each with its own personalities. If I had a say in it, they’d each have their own distinction, because I love them all.

Yue Cuisine takes a lot of pride in using ultra-fresh ingredients. I once visited a fish market in Hong Kong, and I was shocked at the sheer variety of live seafood. There were fish and seafood items in all sizes, shapes, and colors—all live (even ocean fish!).

In terms of cooking techniques, preparation is simple and thoughtful, using methods like steaming, poaching, and simmering to highlight the pure flavor of each ingredient in the dish. In Cantonese soups, the simplicity of the broth is the star.

The popular description of Cantonese cuisine is that it’s clear but not bland, fresh yet refined, and oily but not greasy. Contributing to this are the creation of wok hei (a smoky seared flavor from stir-frying at very high heat) and precise cooking times down to the second.

(If you’ve ever tried making Cantonese steamed fish, you know that even a few extra seconds of cooking time can turn perfectly tender fish into slightly overcooked fish.)

Bill’s parents were from Guangdong, so many of the cooking techniques and recipes we share on The Woks of Life are a reflection of Yue cuisine.

If you’d like to try making some classic Cantonese dishes, get going with Cantonese Steamed Fish, Cantonese Roast Pork, White Cut Chicken, Char Siu, and Watercress Pork Bone Soup. Dim Sum also hails from this cuisine, so try out our collection of dim sum recipes as well!

4. Su (Jiangsu) Cuisine (苏菜 – sū cài):

Su Cuisine, from Jiangsu Province, encompasses Jinling (Jīnlíng – 金陵, a.k.a. Nanjing) cuisine, Huaiyang (Huái yáng – 淮扬) cuisine, and Suxi (Sū xī – 苏锡, a.k.a. Suzhou & Wuxi) cuisine.

My personal favorite is Huaiyang cuisine, renowned for intricate knife skills and meticulous preparations. To give you an idea of what this means, I’m thinking of one captivating image from a Chinese television program called A Bite of China. Chefs were training to cut silken tofu into hair-like strands—thin enough to thread through a sewing needle—for a local specialty soup called Wensi Tofu Soup. Using a big heavy cleaver, no less.

Like Yue cuisine, Su cuisine seeks to highlight the flavor of the original ingredients. The flavors are very subtle, yet tantalizing, bursting with umami. But when it comes to braised dishes, like Wuxi Ribs, generous use of vinegar, sugar, and rice wine (黄酒 – huángjiǔ) really sets this cuisine apart. You will also find wide uses of Zhenjiang vinegar, which comes from the region.

Another distinction of Su cuisine is in its presentation. Their famous sweet and sour squirrel fish is a work of art on the plate, requiring great skill to execute. That wensi tofu soup that I mentioned earlier is like a water-color impressionist painting in a tureen. No wonder the beauty of Su cuisine has gained a place on China’s state dinner tables for decades.

To name a few Su cuisine recipes we’ve shared on the blog: Sweet and Sour Squirrel Fish, Lion’s Head Meatballs, Nanjing Salted Duck, Young Chow Fried Rice, Sweet and Sour Ribs, Shanghai Scallion Pancakes, Shanghai Spring Rolls, and Soup Dumplings.

Su Cuisine greatly influenced much of the Shanghainese cuisine (běn bāng cài – 本帮菜) that I grew up with. (Along with Zhe Cuisine, #8 on this list, as Shanghai borders Jiangsu Province to the northwest and Zhejiang Province to the southwest.)

Note!

The four cuisines above were the four major cuisines of China before the Qing Dynasty, which is why they are collectively known as the Four Great Traditions of Chinese Cuisine (Lu, Chuan, Yue, and Huaiyang). Think of the next four cuisines as the newcomers, established around the end of Qing Dynasty to form the major eight.

5. Min (Fujian) Cuisine (闽菜 – mǐncài):

Min Cuisine is from the southeastern coastal province of Fujian. It features the best that both land and sea have to offer. Like most of the cuisines on this list, there are several sub-styles.

In the capital city of Fuzhou, the food is light and fresh. Farther from the coast, in western Fujian, there are more meat than seafood dishes. In southern Fujian, you’ll find Hokkien cuisine, which has influenced (through migration) the cuisines of Southeast Asia and Taiwan. There is also Putian cuisine, which has a focus on seafood.

In many parts of Fujian, a meal is not a meal without a soup. Their most esteemed soup—also perhaps the most famous soup in China—has a very unusual name. “Buddha/Monk Jumps Over the Wall” (fó tiào qiáng – 佛跳墙).

The name suggests that it’s so tantalizing that a monk would break all restraint and jump over the monastery wall to have a taste!

It takes a few days to make this soup, with several very expensive ingredients from both land and sea. Some include jinhua ham, chicken, pork, shiitake mushrooms, fresh bamboo shoots, abalone, sea cucumber, dried scallops, and dried fish maw.

With all these extravagant ingredients, you can expect to pay an arm and a leg for a bowl. The broth is clear, but the flavor is equally delicate, rich, and powerful. It’s worthy of its #1 post.

Fujian cuisine also uses rice wine to make “drunken” dishes, fermented rice wine to make brines, and fermented red yeast rice sauce to braise, as well as seafood-based condiments like fish sauce, shrimp paste, and shacha sauce.

All these ingredients add a distinctive flavor and unique strong aromas special to that region. Come to think of it, I do have a jar of fermented red yeast rice sauce to use up!

6. Hui (Anhui) Cuisine (徽菜 – huī cài):

Hui Cuisine originated in the relatively small, landlocked province of Anhui, located on the Yangtze and Huaihe rivers. It features braises and stews and fewer stir-fries than other regional cuisines.

It feels like “country” cuisine. Wild herbs, mushrooms, and vegetables, game, tofu, and ham all feature prominently.

We traveled to Anhui to visit the famous Yellow Mountain range (黄山 – huángshān). There, we made a side trip to the village of Hongcun (hóng cūn – 宏村). (Fun fact: it’s where they filmed some of the movie, Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon!) That should give you an idea of what this province is like—beautiful mountains, small villages, and bamboo forests.

In Hongcun, we sampled some home-cooked dishes that gave us a real feel for Anhui cuisine. Sarah, Bill and I (Kaitlin was in college at the time) were walking around the village like a bunch of tourists, admiring the canals that ran through the village and the small, well-tended vegetable gardens next to each home.

Besides the unique placement and shape of each family’s vegetable patch, we also peeked into open courtyard doors to see that most families also had a half-carved ham hanging in the courtyard!

A friendly lady had just picked two squashes from her robust garden as we were walking by. We started chatting, and the next thing we knew, we were in her home eating our second lunch of the day.

She and her husband ran their home as a bed and breakfast. They whipped up four delicious dishes, that we had no problem picking clean:

- Steamed bamboo tenders (I call it “tenders” because I don’t know the English word to describe it. They are the lower covered portion of the individual layers outside the bamboo shoots) with their own homemade cured ham.

- Tender squash with garlic in a clear sauce.

- A homestyle tofu dish.

- And some delicious stir-fried wild greens that I don’t know the name of!

It was all so delicious. I still cook that steamed ham and bamboo dish to this day. But it’s never as good as the pinnacle of the innkeepers’ version with homemade ham and fresh bamboo.

There are two other popular Hui dishes that often come up in conversation about this cuisine. One is Smelly Mandarin Fish (chòu guì yú – 臭鳜鱼) with spicy bean sauce. The other is Hairy Tofu (chòu dòufu – 臭豆腐), AKA stinky tofu. While stinky tofu is popular in other parts of China, it originated here.

On our blog, we also have a recipe for Egg Dumplings, which are associated with Anhui.

7. Xiang (Hunan) Cuisine (湘菜 – xiāngcài):

Like Sichuan cuisine, Xiang Cuisine (AKA Hunan cuisine) is heavy on the oil, salt, spicy chilies, and garlic. If you like spicy food, but can do without the numbing Sichuan peppercorns, Hunan cuisine should be your top choice. People describe the flavor as “gān là – 干辣,” meaning “dry spicy,” or purely spicy.

My favorite restaurant is a not-too-fancy, family-owned Hunan restaurant in New Jersey – Fortune Cookies in Bridgewater. My firsthand eating experience is that Hunan cuisine uses a lot of aged/salted ingredients.

Those include smoked beef and pork, fermented black beans, salted or pickled chilies, pickled garlic, pickled long beans, and other more rare ingredients like dried white chilies, smoked bamboo shoots, and dried long beans.

Many families prepare all these ingredients on their own, like the woman who runs Fortune Cookies. She makes her own pickled long beans and chilies that they use in their restaurant cooking.

If you’re wondering if Xiang cuisine has regional sub-styles, yes it does! They include: Xiang River Style, Dongting Lake Style, and Western Hunan style.

Unlike the fancy, refined, and intricate Lu and Su cuisines, Hunan cuisine is humble, modest, and seasonal. It feels most like home-cooking.

While no dish is exorbitantly expensive or extravagant, Hunan is a major agricultural center, so the cuisine uses a wide variety of produce. Many ingredients are specialties of the region. Skillful chefs artfully create distinctively fragrant and fiery flavors.

We have really come to love Hunan cuisine and feature it in several recipes on the blog. Some of our favorite Hunan dishes are: Steamed Fish with Salted Chilies, Pickled Long Beans with Minced Pork, Pork and Pepper Stir-fry, and Homemade Duo Jiao (Chopped Salted Chilies).

We also love dishes like smoked pork with dried long beans, and sautéed preserved eggs with chilies, which we will have to blog in the future!

8. Zhe (Zhejiang) Cuisine (浙菜 – zhè cài):

Zhejiang is a coastal province with many rivers. In Chinese, it’s often called the land of fish and rice—or the land of plenty—(yúmǐzhīxiāng – 鱼米之乡).

The cuisine utilizes a vast selection of fish and shellfish from both the ocean and its many freshwater rivers. When it comes to seafood, chefs employ steaming, pan-frying, braising, salting, brining, drunken-ing, and chilling techniques.

Some other key ingredients come from this province. Zhejiang produces the famous Jinhua ham in the city of…you guessed it, Jinhua. Several of our recipes call for it (though American country ham is a decent substitute!).

Shaoxing wine was also born in the city of Shaoxing in Zhejiang. It has become the preferred cooking wine in many Chinese kitchens, including ours! Shaoxing wine really elevates a dish and enriches flavors without overpowering the freshness of the ingredients.

In Hangzhou, you’ll see many sweet dishes. People in the southeast—like the city of Ningbo—like their food salty. My father’s family was originally from Ningbo, and I grew up on salty food.

We used a lot of salt and soy sauce in daily cooking, partially so that we would eat less! A dish of braised bok choy with both light soy sauce and dark soy sauce is a good example. You can’t eat too much of it, because it’s so salty.

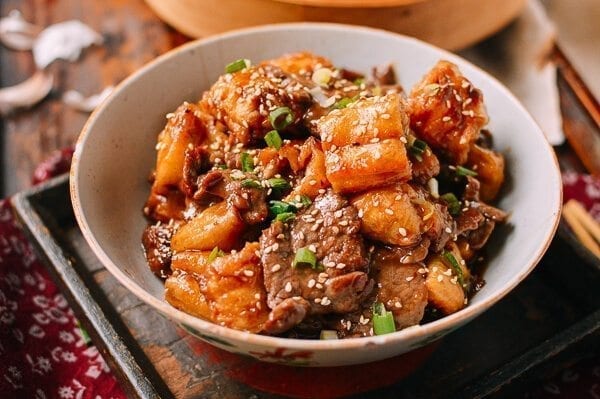

To name a few more well-known dishes from Zhe cuisine: Hangzhou’s Shrimp with Longjing Tea, Ningbo’s Drunken Crab, Dong Po Pork, Beggar’s Chicken, and West Lake Beef Soup. We also had a delicious beef stir-fry with pieces of youtiao (fried dough) at a Zhejiang restaurant in Beijing. It was so memorable, that we blogged the recipe!

Conclusion

We hope that this article has demonstrated just how vast and varied Chinese cuisine really is.

While this article took us a while to write, we have barely even scratched the surface! These 8 cuisines do not encompass all that China has to offer in terms of food. Again, there are many regions that aren’t represented in this list. Futhermore, new recipes are being developed every day!

As you can see, there is still so much to sample, discover, and uncover. With thousands of years of culinary insight and know-how, rest assured that we’ll never get to the end of it. Wok on!