After developing recipes for 10 years now, I feel like I’ve gained a better intuition when it comes to cooking with garlic in just about any kind of dish or flavor combination. It’s also worth stating outright that Chinese food explores the full spectrum of garlic in a way that I think is uniquely robust.

Whole, crushed, chopped, minced, deep-fried or sizzled with scalding hot oil right before a dish hits the table…if you cook enough Chinese food, you’ll see garlic in just about every iteration.

So, today I wanted to take some time to cover various methods of cooking with garlic, because I feel like I’ve come a long way from the rudimentary, toss-it-into-the-hot-oil-and-then-proceed-with-the-recipe conventional wisdom.

cooking with garlic 101

Use the links below to skip ahead to specific questions in this post:

- Garlic as the first step

- “Late stage garlic” (*If you only read one thing from this post, head here!)

- Caramelized garlic

- Garlic infusions

- Sweated garlic

- Raw garlic

- Sizzled garlic (*This may be an MVP of Chinese cooking techniques!)

- Fried garlic

- Pickled and fermented garlic

- What’s the best way to peel garlic?

- Different ways to cut garlic (crushed, chopped, minced, sliced, extra fine/pureed)

To learn more about other aromatics commonly used in Chinese cooking, check out our fresh herbs & aromatics page in our Ingredients Glossary!

Make Your garlic work harder

If you checked in with us in the early 2000s (I would have been in middle school, a mere disciple of food television) and asked how one should prepare garlic, you probably would have gotten the canned answer: “caramelize it in some oil.”

But there’s SO much more to cooking with garlic—much of it revealed only as we’ve set out on our decade-long journey deeper into Chinese cooking.

Garlic’s dimensions are so much broader than just a blended note in a stew or braise. In fact, more often than not in Chinese cooking, we are chasing that fresh garlic aroma—or in some very tasty cases, the outright spicy bite of raw garlic.

Learning more about cooking with garlic isn’t just good for the end result of your kitchen labors. It’s also good for your wallet. The other day, my mom and I were in the kitchen chatting about how expensive garlic has gotten, just like everything else! It’s more important than ever that we make this pantry ingredient work even harder for us.

I know that the cost of garlic at the corner store has me using it much more carefully and deliberately than I used to. (I guess lamenting the rising prices of garlic is what getting older looks like. Next time you doubt your “adulting” skills, remember moments like this.)

How to Tell when you’ve burned your garlic

Many of us already know the cardinal rule: Burnt garlic means bitter results. Bitterness that can often permeate the entire dish!

Garlic burns very easily, and when it burns, it turns bitter. But how can you tell when it’s burnt? If you take nothing else away from this post, take this: you might think of burnt garlic and picture a blackened mess—which…well, yes—but garlic is also like cookies.

As I learned from Alton Brown’s OG Good Eats—cookies are burnt even when just the edges are darkened and crisp. To an untrained eye, they may not look burnt, but burnt they are. Similarly, garlic is burned when it turns just a few shades too brown.

When frying garlic, remove it from the oil when it has lightly turned color, as the residual heat continues the frying process. Remove it too late, and it will taste bitter.

If you accidentally burn your garlic, and you’re early on in the cooking process, it’s actually better to start over with new oil and new garlic than to push through.

Cooking with garlic: When to add it to the pan

1. Garlic as the first step

This is what most people expect to do when cooking with garlic. When you cook the garlic a bit in some oil before adding other ingredients, it has a chance to mellow and get that hint of sweetness, and also has a chance to lightly infuse the oil. It’s the same reason why many recipes often start with the onions before anything else.

We do often take this approach, like when we’re cooking a wokful of leafy greens.

Here are some pointers, for when this approach is called for: Move quickly. We heat the wok until it’s just smoking, add the oil (remember, “hot wok, cold oil”), followed by the garlic, and then pretty much immediately add the vegetables to avoid any burning garlic and to preserve a fresh taste.

Or 2. Late Stage Garlic (i.e. adding it later in the cooking process)

This is the single-most important kitchen discovery I’ve had in the last year, and the reason why we wanted to write this post!

It’s something I realized from eating at our favorite Chinese restaurants, where ingredients hit woks heated by tens of thousands of BTUs.

Chefs add the garlic later in cooking, and before it has a chance to brown, let alone burn or get any hint of “caramel” note, the food is on the plate and headed for the table.

The result is a very fresh, yet also cooked garlic flavor, where you get the best of both worlds—a little sweetness, but with lots of punchy garlic flavor.

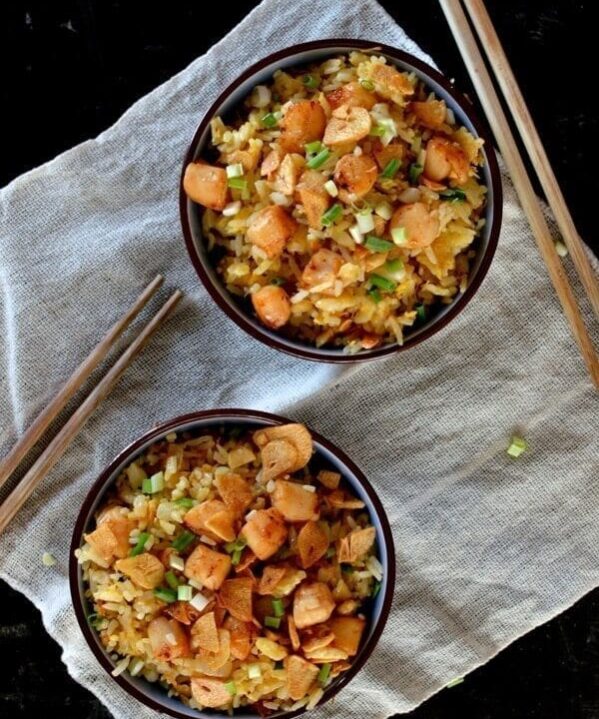

Recipes that use this technique include our Thai Fried Rice, Kung Pao Beef, and Stir-fried Celtuce with Wood Ear Mushrooms.

If you’ve added your garlic first, its flavor has potentially receded too far into the background of the dish by serving time. Or it’s mellowed to the point of losing that garlic-forward flavor.

By adding the garlic at a later stage in the cooking process, you can get the bright flavor of garlic even while it permeates the dish. So instead of adding it to the oil at the start of cooking a vegetable stir-fry, try adding it mid-way (or even later depending on your preference) so the garlic doesn’t lose that zing by the time the vegetables and meat are cooked.

This is especially effective when pickled and sour ingredients are involved, like pickled long beans, haam choy, and pickled mustard greens (xue cai).

How to cook Garlic

“Caramelized” garlic

This is probably what many of you would think of when cooking garlic. You add the garlic to hot oil and let it get slightly browned around the edges.

We don’t recommend this often, because garlic that has a chance to darken can turn bitter and unpleasant. It’s why you’ll often see our recipes call for cooking ginger or onions first, before adding the garlic.

A way to get truly caramelized garlic without burning it is slow-roasting it in the oven, as in Sarah’s Chicken Fettuccine Alfredo with Roasted Garlic. (More on this later.)

Garlic infusions

Of course, the purpose of adding garlic to hot oil in stir-fries and sautés is to infuse the dish with flavor, but I’m talking about a more deliberate infusion of larger quantities of oil, like in our chili oil!

Ever since we started adding a couple garlic cloves to our oil infusions, our chili oil has gotten that much more fragrant and delicious.

(Just be sure to read up on food safety tips, as introducing fresh ingredients into an anaerobic environment does have implications for shelf life and storage.)

Sweated garlic

No I’m not talking about when you get the garlic sweats. Similar to sweating an onion, this is when you cook the garlic to deepen and mellow the flavors for an extended amount of time without actually browning it.

This step doesn’t take long, as you’ll see in our Cooked Lettuce with Oyster Sauce and Garlic and Chili Garlic Shrimp!

Raw garlic

When you think of raw garlic—lots of articles come up on the health benefits, but fewer come up on the merits of the flavor!

Beijingers love raw garlic. In bao and dumpling houses, you’ll often find a little pot of minced garlic alongside soy sauce and chili oil for dipping your pan-fried baozi in. (See our carrot ginger pork buns.)

Also see the use of raw garlic in the dipping sauce for my mom’s Northern Chinese Pork Belly Stew with Sour Cabbage.

Raw garlic is also a key ingredient in reader favorites like Smashed Cucumber Salad. Some things in life are just more important than whether you’ve got garlic breath.

As we’ll talk about in the next section, lots of Chinese dishes par-cook garlic—whether that’s by adding it right before serving or pouring hot oil over the top. An intermediate between raw garlic and “sizzled” garlic (see next section) is featured in my mom’s taro rice.

The raw garlic goes in at the very end, stirred into the hot cooked rice mixture. The result is an aromatic garlic flavor that infuses the entire dish! This is one of our favorite recipes of the last year.

Sizzled garlic

One of the most valuable techniques we discovered from our time living in China was the practice of heating a small amount of oil and pouring it over aromatics like garlic or ginger/scallions in a dish like Cantonese steamed fish.

You’ll see this method in our Sichuan Boiled Beef (shuizhu niurou) and a recipe from our cookbook (below center) for Golden Soup with Shaved Beef.

It adds umami and just takes the raw edge off. Simpler recipes that use this technique are noodle recipes like you po mian and my mom’s Chinese Ban Fan (Mixed Rice Bowls).

Fried garlic

Crispy fried garlic is a mainstay of some of our favorite Cantonese dishes. If you’ve ever enjoyed salt and pepper smelts with crispy fried garlic and shallots over the top, salt and pepper tofu, or a dish like typhoon shelter shrimp, we have more information on how to fry garlic in those recipe posts.

There are also times where we fry garlic over a very low flame. Two notable recipes are our XO Sauce and Chiu Chow Chili Sauce, which are heavy on the garlic!

Pickled And Fermented garlic

Pickling and/or fermenting garlic (they are not the same) is the method in this list that we’ve technically probably explored the least. It does show up in my mom’s pickled cabbage restaurant appetizer, however!

Just know that pickling entails adding garlic to an acidic/sour medium, i.e., vinegar and fermenting is a process that yields that sour flavor without adding any acid. Our fermentation efforts are still somewhat young, but rest assured it’s on the ol’ “to cook” list! (For anyone interested, see our fermented Hunan salted chilies recipe!)

My roasted garlic era

As I write this, with Taylor Swift serenading me through her many eras of music, I walk down memory lane to my roasted garlic era. There was a period of time when I was a teenager, during which I have remarkably numerous memories of cutting a whole head of garlic in half, covering it in oil, crumpling it inside a ball of foil, and popping it into our toaster oven.

We were obsessed. Shmearing it on bread, mashing it into dipping oil to eat with golden toasted grocery store Portuguese rolls—we made it often.

(In case you don’t believe me, see here a cameo in our soy butter glazed ribeye recipe from 2015.)

Looking back, though, I feel like I enjoyed the ritual of making it more than the actual end product, as I don’t have many memories of actually eating said garlic.

Sadly, time has rendered roasted garlic a little bit forgettable. Perhaps proof that garlic is simply better zingy and spicy than sweet and caramelized?! Come after me in the comments, if you need to!

Preparing garlic Before Cooking

The best way to peel garlic

There’s been a lot of examination on the best ways to peel garlic. I’ve done all the doofy stuff, like shaking garlic cloves around in a covered bowl, rolling it here and there, and stabbing it with a paring knife.

The best method is crushing it under the side of your knife. (Just use a moderate or gentle amount of force with your palm or a fist—knives can break if you hit them the wrong way. Just ask my mother—yeah, don’t mess with her!)

If you remove the woody end first, the garlic skin comes off even more easily, but sometimes if you leave it on, it actually can make it easier to remove the garlic skin all in one piece.

If you have one of those garlic silicon gizmos, feel free to use it, but I think shoving garlic cloves into a tiny little tube is just as annoying as smashing it, and you have one extra thing to wash at the end of the day.

Fresh Garlic is best!

Fresh garlic is always better than jarred. You can save money if you buy it in bulk or head to Asian grocery stores. Jarred garlic is acidified to preserve freshness and prevent bacterial growth, which changes its flavor and texture.

If the jarred stuff is all you have, just know that you’ll want to invest in fresh garlic whenever we call for it in its raw state.

Do I have to remove the Tough STem Part of the garlic clove?

I usually remove the tough end that forms the base of the head of garlic. Beyond that, I really don’t think there’s a huge need to meticulously cut every end off of every garlic clove—just the extra tough bits.

It depends on the application—if you’re eating it raw, removal is ideal. If it’s just a small amount, you can be a little more lax, and no one will be the wiser.

After peeling, let’s talk about different preparations:

Crushed garlic cloveS

More is not always more. I have come to learn the virtues of restraint in cooking with garlic. Sometimes a few smashed cloves (say in a pot of Taiwanese Beef Noodle Soup) are all you need, and it’s better to leave it in one piece so that you don’t end up with errant bits in your soup.

(A few crushed cloves tossed straight into a pot of marinara also helps yield a fresh-tasting, tomato-forward marinara.)

CHOPPED garlic

Oftentimes, a simple rough chop of garlic will suffice, and there’s really no need to make it fancy or difficult. Strictly speaking, no one needs to ~brunoise~ a garlic clove if you ask us.

Start by crushing the garlic clove to make it less slippery and get you halfway to chopped, then run a knife through from there.

Minced garlic

However, much of the time in Chinese cooking, minced garlic is ideal. This is the case in dipping sauces, noodles, cold dishes, and sometimes stir-fries, when you don’t want to bite down on a bigger chunk of garlic.

This is particularly relevant in dishes where you add garlic later in the recipe.

To do this, we usually use either a garlic press, a Chinese cleaver, or even the food processor if there’s really a lot of garlic to work through.

I’ve found that it’s easier to mince garlic with a cleaver because the heavier weight of the cleaver seems to prevent small bits of garlic from flying off your cutting board when you make rapid cuts.

Sliced garlic

Sometimes it’s nice to have garlicky “chips” that are pleasing to the eye and to eat. Notably, Sarah uses this technique in her Asian Garlic Noodles and Spicy Garlic Tofu, and you’ll often see it when deep frying garlic.

EXTRA FINE / PUREED garlic

It’s rare that an old-school Chinese recipe will ask for anything pureed. The work of a cleaver can yield a fine enough mince, and it’s simply not necessary.

That said, grated or pureed garlic can be useful in meat marinades where big chunks of garlic can burn in the oven or disrupt the texture of the meat.

When making our grandpa’s turkey recipe for Thanksgiving, I throw the garlic and oil into a food processor to make a paste! And in our Taiwanese Pork Chop Plate, we use a microplane to grate the garlic.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this discussion on cooking with garlic, and that you now have some new ideas and perhaps a few recipes to try. Questions? Let us know in the comments below!